In August 2019, I planted 1200 banana saplings in a Jharkhand village.

The banana plants are spread over 2 acres and have grown in number to 1500. But the plants have caught the Panama wilt disease. They still bear edible fruit but the growth will be stunted for the plants themselves. In other words, they won’t produce as much fruit as they could have. That was disappointing, but also instructive. There are learnings from this experience that might be useful in the future.

My father has built this temple in the village. Around it sits a small community space, cow sheds that now house more than forty cows, a school, a clinic for medical check-ups, and quarters for visitors and temple workers.

Beyond the temple complex lies 50 acres of vacant farmland. The soil is fertile, and there’s reliable stream water for irrigation. On paper, it looks perfect for crops or for planting forests.

So why is it still empty?

I live and work in Bangalore. And while my parents are in Calcutta, and they are always on the move. Over the past three decades, there have been many Farmville-esque attempts to bring the land into use. Each time, the realisation has been the same:

पूत बाढे पिता के धर्मा और खेती बाढे निज के कर्मा।

If you are not physically present on your land, farming rarely works out. At least not if your goal is to make a living from it. But I wasn’t aiming to make a livelihood. My goal was simpler: to plant more trees. That felt doable, even from a distance.

Here is the plan I came up with:

- Identify and procure the trees I want to plant

- Assign the responsibility to take care of the trees to a new farm help

- Use 2 acres of farmland to run this experiment

- Wire-fence the land parcel

- Monetise the activity so it can fund the next batch of trees or support social impact work.

Why Bananas?

Bananas are well suited to the climate and soil. Almost every part of the plant – flowers, stems, fruits, leaves can be put to use. And if nothing else, they are easy to sell.

I reached out to Keventer’s company head, Mayank, who kindly connected me with his team. They visited the farm, tested the soil, and gave me a feasibility report. Soon, I had saplings in hand and the experiment began. Over the next thirty months, I learned how much I didn’t know about farming. Elephant grass ran wild, irrigation was patchy, and infected plants weren’t pruned in time. The yield was modest.

Banana Fun Fact

Alexander is said to have first encountered bananas (along with apples) when he marched into India 2300 years ago. What began as a curiosity for his soldiers soon traveled westward through trade routes, spreading to the Middle East, Africa, and eventually Europe.

I had considered different approaches: Permaculture, Miyawaki forests, and other methods as possible routes to add green coverage. Each had its appeal. Permaculture promised self-sustaining ecosystems, while Miyawaki forests offered rapid results in dense patches of greenery. But the more I read, the clearer it became that both carried a web of variables – soil conditions, biodiversity balance, long-term upkeep, and the need for skilled hands on the ground. For someone trying to work from a distance, these complexities risked becoming barriers instead of bridges.

In the end, I chose the simplest path: start small, plant trees, and keep going.

The bananas I planted were Cavendish, the same variety that most of the world now consumes. They’re productive, but also fragile, with little resistance to disease. Contrast that with native Indian wild bananas, which are hardier but less commercial.

Wins beyond the harvest (updated in Sep 2025)

If I only measured success by output or income, this first banana experiment didn’t hit the mark. But I’ve come to see success not in tons of bananas harvested but in what the land has gained. The fields quite literally look greener today.

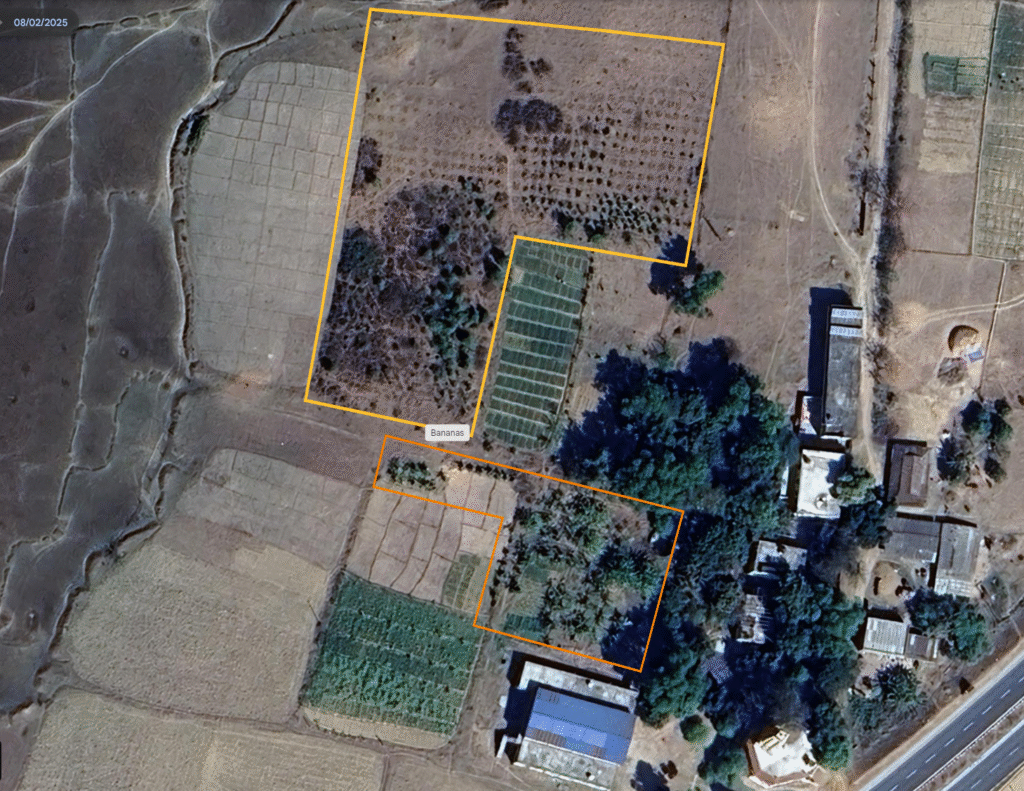

There is more organic matter in the soil, more shade, and more resilience built in. Even modest tree cover can increase soil carbon, retain more water, and bring down surface temperatures. You don’t need a soil scientist to tell you that. You can feel it underfoot. I have walked the land in peak summers before and it was scorching, like standing on a hot plate. Now, with even this small patch of tree cover, it feels cooler, more forgiving. Historical satellite images tell the story too: what was once dry, arid brown is now shaded green.

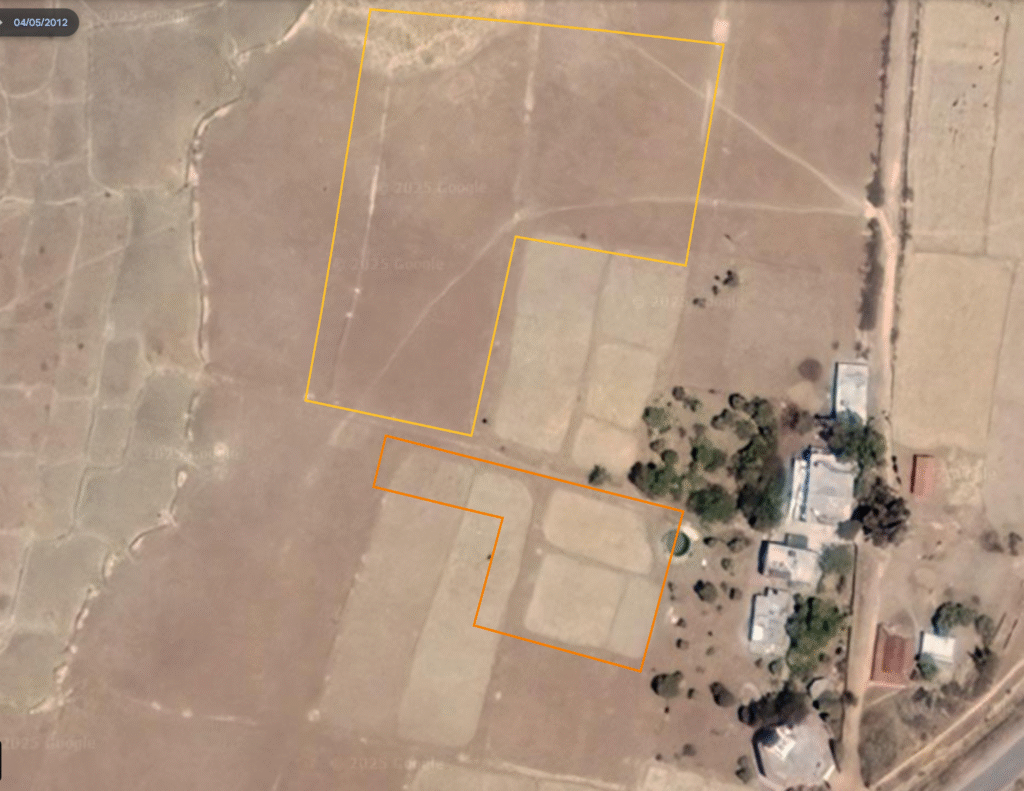

Here is a satellite image from 2012. Earlier images exist, but they are too blurry to make out much detail.

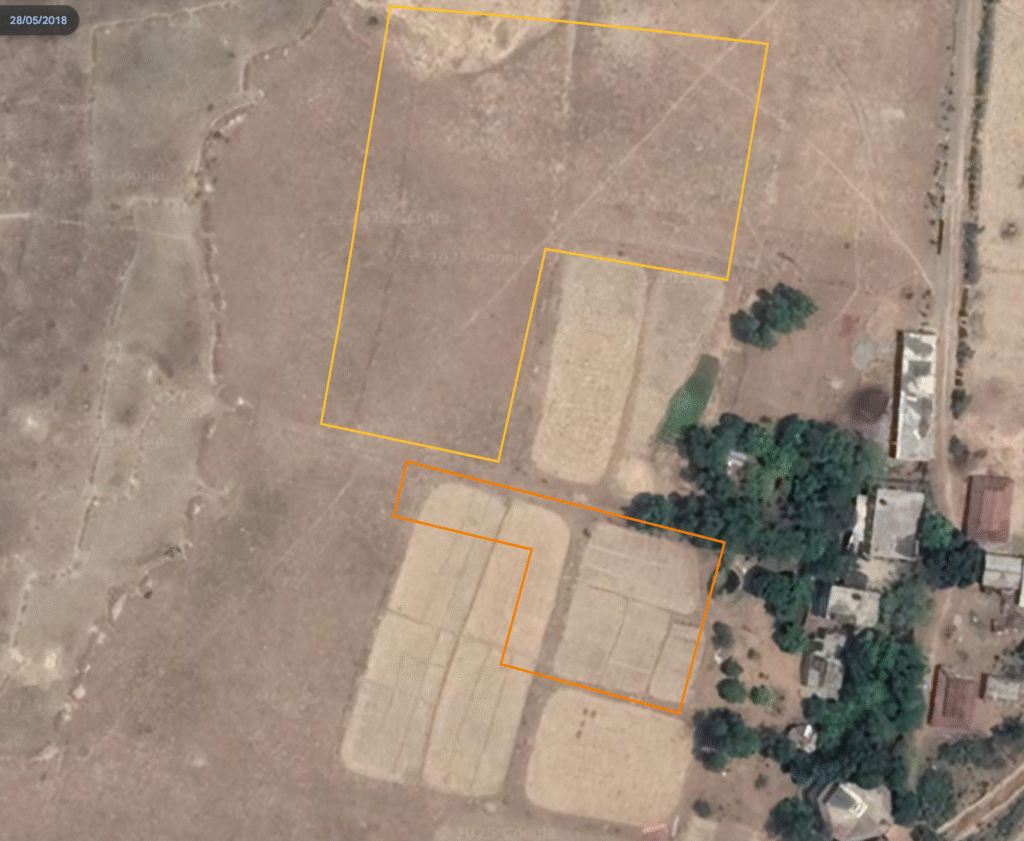

Nothing changed in this section of the land over many years. Here is another image from 2018, thats the year before I planted the trees.

And this is the present-day picture 🙂

Within the yellow outline lie the Cavendish bananas I planted, and in orange, the Indian wild bananas. Around them are the many fruit trees and crops my father planted and they have done far better than my experiments. 😅

Meanwhile, this green shift is far from cosmetic. One change I have noticed is in the soil itself. What used to feel dry and lifeless now has more organic matter – bits of fallen leaves, banana stems, cow dung, and the small army of microbes and earthworms breaking it all down. This is what scientists call soil organic matter, and it is what gives rich soil its dark, crumbly texture. The more organic matter there is, the better the land behaves. It holds on to rainwater like a sponge, releases nutrients slowly to the plants, and keeps the ground from turning into hard crust under the sun. Even a 1% increase can mean thousands of extra liters of water stored per acre. There are simple tests to prove it but you can simply feel it in the fields.

That’s why summers feel different now. Earlier the land burned underfoot; now it stays cooler and softer. The trees provide shade above, and the soil holds moisture below. It’s a small but real sign that the experiment is working, not just in plants harvested but in the climate resilience being built into the land.

And it is not just me who feels the difference. The cows are happier too. Here are some of them grazing in the open.

They linger under the shade, graze longer, and need less water through the day. It is a small reminder that climate action does not always have to be abstract or global. Sometimes it is as close as noticing that the summer sun burns a little less when there are trees standing between you and the sky.